This article is first published in the Myanmar Times on December 2, 2019.

Myanmar’s state-owned banks (SOBs) are currently at a crossroads. Following the opening-up of the banking system, the SOBs have been pushed to catch up with rapidly-growing private banks, many of which have invested in technology, digitizing operations and expanding mobile services.

Responding to competition, the four SOBs are taking steps to diversify their loan portfolios, including to accommodate rising loan demand in the rural areas, as identified in AMRO’s 2019 Annual Consultation Report on Myanmar. The SOBs have also expressed intentions to modernize and enhance efficiency through investments in staff development and information technology. Limited staff capabilities such as in assessing credit risks as well as outdated banking infrastructure have weighed on SOBs’ financial performance.

The reform efforts by the SOBs are encouraging, but the SOBs should aim to respond to the needs of the businesses and households that have long been neglected by the financial system in Myanmar. Indeed, even as private banks have expanded rapidly in Myanmar, overall access to finance remains low. According to a 2017 survey by the World Bank, only about one in four adults have access to financial services, with rates even lower in rural areas. Bank credit is concentrated in construction, trade and services, hindering the vibrant manufacturing sector from moving to a higher level of development. A meager 7 percent of small and medium-sized enterprises have a line of credit or loan, and a similar survey by the Ministry of Planning and Finance in 2017 found that close to 80 percent of the starting capital of businesses was self-funded.

It is thus no surprise that the lack of access to credit has been identified as a major constraint to doing business in Myanmar. These days, financing access is further held back as the banking system is building up buffers to comply with stricter prudential regulations. Against this backdrop, the SOBs have a major role to play in bridging the country’s financing gaps. However, realizing their full potential would require a national agenda to restructure the SOBs. This is in fact part of the government’s broad program to develop a competitive, sound and inclusive financial sector.

Take the case of Myanmar Economic Bank, the largest SOB. The bank has been performing a dual role, providing banking services to government agencies (including the distribution of pension) as the state’s treasury, while assuming some development functions, extending concessional loans to the Myanmar Agricultural Development Bank, of which its coverage of about two million farmers can be significantly improved. The current functions of Myanmar Economic Bank, as with the other SOBs, can be revisited while their development functions strengthened, and the SOBs can consequently play a strategic and vital role in Myanmar’s economic transformation.

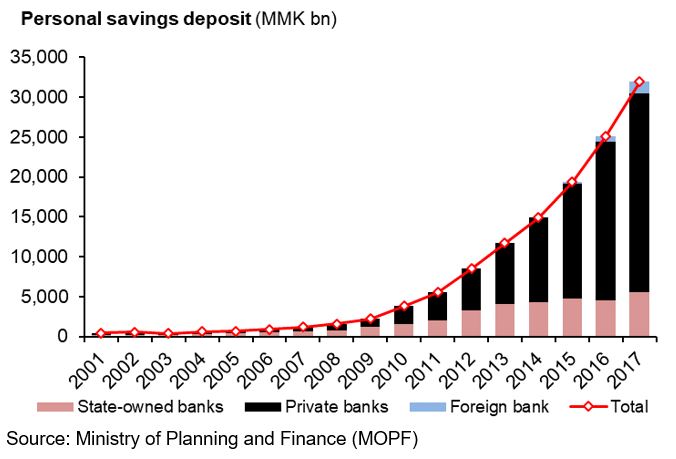

SOBs are lagging behind the competition. Between 2005 and 2017, SOBs’ share in personal savings deposits fell from 61 percent to 18 percent within the same period, with the rapid growth in savings absorbed by the private banks.

For example, the SOBs—once transformed into a profitable retail commercial bank, as currently being explored for two of the SOBs—would have a greater capacity to support micro, small and medium-sized enterprises, such as farmers and small and innovative companies, which are deemed not creditworthy or viable by the private banks. Some of the SOBs could likewise transform into development banks as also under consideration currently, taking part in long-term financing of enterprises in some strategically important sectors or large-scale projects, which are deemed too risky by the private banks. Moreover, they could help to counteract the procyclical nature of private banks’ lending, thereby providing some relief to businesses during economic downturns.

Myanmar can draw inspiration from the success of fellow Southeast Asian countries like Indonesia and Thailand. In 1980s, Bank Rakyat Indonesia transformed itself from a heavily-subsidized institution into one of the most globally-profitable banks by the mid‑2000s with a continued focus on micro loans. The Thai Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Cooperatives has become self-reliant while extending finance to 95 percent of Thai farming households. However, it must be highlighted that these banks took a few decades to attain sound financial health.

Likewise, national development banks have been shown to be instrumental in supporting long-term development strategies, such as in the case of Korea, China, and India. A key success feature of their role in economic development, it appears, is their ability to shift gears with regard to priority activities once development crosses a certain threshold, or in response to the prevailing environment at the time.

Going forward, developing financially-viable and effective SOBs would require the need to create an enabling environment that will offer incentives for reform. Indeed, there is a lot to be done, but it is encouraging to see reforms in the overall financial system gradually taking shape.