By Chuin Hwei Ng

Asia is often thought of as a manufacturing powerhouse, and integration into the global economy via trade has indeed lifted all ASEAN+3 economies in the past decades. But since the Global Financial Crisis, export growth has slowed markedly and job creation has been sluggish. While sluggish demand from slowing advanced economies had certainly exerted a drag on exports of ASEAN+3 economies, other more fundamental factors such automation and digital technology are also at work.

In this context, AMRO’s recently-released flagship report, the ASEAN+3 Regional Economic Outlook (AREO) 2018, suggests that while the ASEAN+3 region deserves credit for harnessing global trade, investment and capital flows to build resilience and growth, there is a need to augment that tried-and-tested export-led growth strategy which has served ASEAN+3 economies so well for so many decades.

Consider these realities.

First, while the “first wave” of economies – Japan, Korea, Hong Kong, and Singapore – and the “second wave” – China and the large ASEAN economies – managed to expand their manufacturing sectors to 25-30% of GDP during their development, most “third wave” economies’ – Cambodia, Lao PDR and Myanmar – manufacturing sectors are likely to top out at 15-20% of GDP. Second, in terms of employment, even while manufacturing’s share has declined from about 40% to 25% in the past 30 years, both the “second wave” and “third wave” economies look like their respective peaks will be much nearer to the “first wave” group’s trough rather than peak. Third, although achieving sustained productivity gains has challenged all ASEAN+3 economies, the services sector has lagged the manufacturing sector in this respect – similar to trends in other emerging regions. In other words, the sectoral shift from manufacturing to services, in and of itself, is no guarantee that the overall pace of growth will be sustained or boosted.

Manufacturing production and trade no longer provide a straightforward route for growth and employment. Where once newly-emerging economies could reap economies of scale, earn foreign exchange and attract investments by producing basic manufactured goods for exports, rapid technological advancements have raised the bar for manufacturing and even more so for participation in global value chains (GVC).

Overall, GVC activities have moderated due to several factors. A combination of a slower pace in tariff reductions and the rapid rise in non-tariff barriers have slowed the momentum of GVC participation. Also, what may work well for individual countries, especially big and rapidly-upskilling countries, may not be as effective for smaller newly-emerging countries. For example, as China continues upgrading its human capital, technological capacity and in-country connectivity, it produces more and more of the intermediate goods used in the production of the final produces. As a result, GVC activities centered around China as a manufacturing hub could decline. There may also be a limit to which supply chains can be fragmented, and for various emerging market economies that are plugged in, labour cost arbitrage opportunities may have been maxed out.

Technology, conventionally seen as a plus for economic development, is proving to be double-edged. Given the stark and rapid nature of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, it is challenging for countries to strike a good balance. Regional economies need to build capacity for technology absorption quickly, yet manage the pace of technology adoption judiciously, so that economic gains from the productivity ramp-up do not override the adverse impact on employment and income. Essentially, “managing” the pace of technology upgrade may be better for near-term economic outcomes than it is for longer-term outcomes. Such an approach may preserve a considerable number of jobs in the near term, buying valuable time for labor market adjustments and averting large-scale layoffs. But if prolonged excessively, it can delay inevitable economic restructuring and labor upskilling and redeployment. Indeed the challenge posed by technology, alongside structural shifts in the nature of cross-border production and trade, may be so stiff that countries which are unprepared risk being cast adrift in the pursuit of growth and resilience.

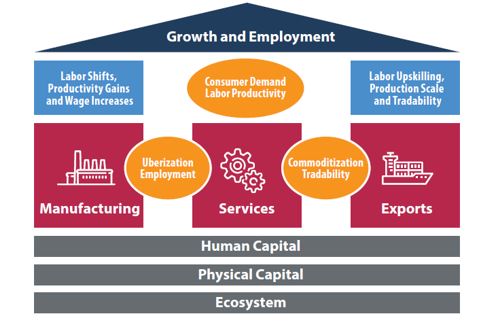

Schema of ASEAN+3 Countries’ Augmented Growth Model

Developing the services sector in a concerted manner has taken on greater importance, as rapidly-changing consumer demand trends and production processes have given this sector a much more prominent role – as a key enabler of manufacturing activity as well as a growth driver and jobs creator. Today, the services sector as a whole already accounts for more than half of GDP and employment in most ASEAN+3 economies. Globally, a wide range of services have become indispensable components of the manufacturing value chain. Research and development, transport and logistics services, marketing and sales are essential to bring goods from the factory floor to consumers (or other manufacturers). Services’ share of exports in value-added terms has risen sharply over the past three decades, and looks set to overtake manufactured goods. Many services today, ranging from call-centre services, accounting, legal and human resource management services to the tourism sector, are also much more tradable than in the past, thanks to the Information, Communications and Technology revolution.

Taken altogether, it is appropriate to rethink and to adopt an augmented “manufacturing for exports” growth model in responses to changes in trade and production networks and technology as suggested in the graphic below.

For individual economies, the key recommendation is to build resilience through multiple engines of growth, including through the growing services sector. The region as a whole should strengthen intra-regional connectivity and integration to meet growing intra-regional demand and improve the resilience of the region against external shocks. Policy efforts should focus on improving connectivity through investment in domestic and intra-regional infrastructure, coupled with trade facilitation policies, and building a vibrant services sector and human capital, including liberalizing the services sector and leveraging on the availability of human capital across the region.

* This article is the second part of a blog series on growth and resilience in the ASEAN+3 region, which includes 10 members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and China; Hong Kong, China; Japan; and Korea. Read Part 1 of the series.