Shrinking demand for loans, an aging population, and a prolonged low-interest-rate environment have hit the profitability of Japan’s regional banks over the last few years. These challenges have prompted the flailing regional banks to look for innovative solutions to survive.

Then came the COVID-19.

Battling structural challenges

Demographic challenges and subdued economic activity in non-metropolitan areas are problems that continue to plague Japan’s regional banks.

In rural communities, many small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which are mostly privately-owned or sole proprietorship, are closing down due to a lack of successors to take over the business. SMEs also have difficulty hiring young workers who are attracted to jobs in the cities.

As a result, the demand for loans in rural areas has been declining year by year.

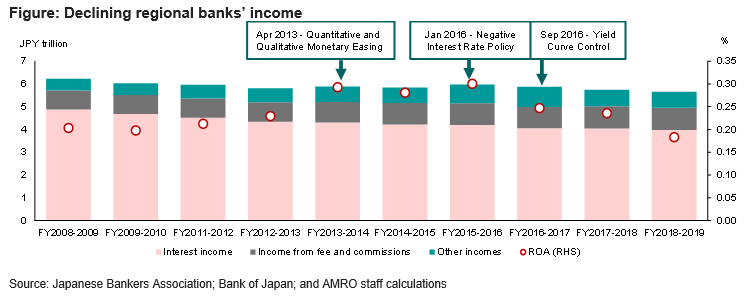

A prolonged period of low-interest-rate environment resulting in a narrow interest rate margin poses another challenge. While many regional banks have turned to investment in riskier assets such as trusts, alternative investment and overseas securities, the returns on these investments are insufficient to offset the shrinking returns from lending.

Moreover, conservative management and inefficient business operations have also contributed to declining profitability.

Although weak earnings are pervasive among regional banks, the pressure is on lower-tier regional banks that have thin capital buffers.

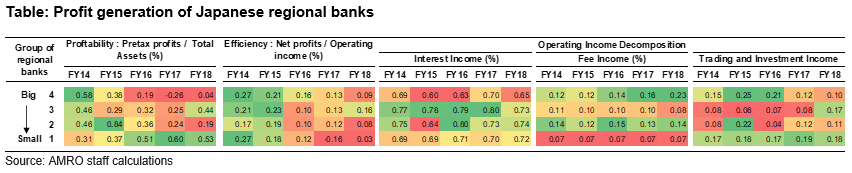

AMRO’s 2019 Annual Consultation Report on Japan found that in a low-interest-rate environment, diversifying sources of revenue and better cost management have enabled first-tier regional banks, classified by asset size, to be more profitable than lower-tier regional banks.

In general, they were able to better manage operating costs and diversify sources of revenue to shore up profitability in a low-interest-rate environment.

The lower-tier regional banks were able to maintain core profitability from lending, but their net profits were dampened by their limited ability to generate income from other sources.

Pandemic menaces the struggling banks

Notwithstanding the existing challenges faced by these banks, the pandemic has compounded their woes by causing financial markets to become turbulent and affecting asset prices.

Following the COVID-19 outbreak, global investors’ risk appetite deteriorated sharply in the middle of March 2020. The global stock markets crashed and securities prices were volatile.

The regional banks’ unrealized gains on asset valuation were sharply reduced due to a plunge in stock prices at home and overseas. However, such losses were partially reversed, as global stock markets rebounded following interventions by the U.S. Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank to support the markets. Some regional banks even gained from the rally in the bond markets, which benefited from monetary easing policies in response to the COVID-19 crisis.

That said, the asset valuation risk remains significant, reflecting concerns over a resurgence in the COVID-19 infections.

As economic fallouts from the COVID-19 pandemic raise credit risks in the financial system, adverse impacts from the worsening credit situation could be the main risk going forward.

In addition, SMEs are hard hit by the COVID-19 crisis due to cash flow problems and a plunge in tourist arrivals, resulting in a dwindling pool of borrowers in small cities and rural areas. Despite the government’s economic relief policies, defaults by the SMEs threaten to rise substantially if the economic downturn is prolonged.

As credit risks and credit costs continue to rise, the problems reflect a continuing trend of falling profits for the regional banks.

Long-term solution lies in consolidation and adjustment of business model

Consolidation could be one of the strategies for the regional banks to survive amid a tough business environment.

Pre-COVID-19, Japan’s regional banks already started merging with one another to expand business and customer base, and improve efficiency. In 2018, Kiraboshi Bank was set up from the consolidation of regional banks based in Tokyo – Tokyo Tomin Bank, Yachiyo Bank, and ShinGinko Tokyo. Kansai Urban Banking Corporation merged with Kinki Osaka Bank in 2019 to become Kansai Mirai Bank, a subsidiary of Resona Holdings.

Partnerships with nonbanks are also on the rise. SBI Holdings, Japan’s biggest financial innovation firm, has actively invested in several regional banks such as Shimane Bank, Fukushima Bank, and Shimizu Bank, which would benefit from SBI’s strength to enhance their IT and online banking systems.

Moving forward, there is more room for further consolidation. AMRO’s analysis found that big and small regional banks employed different business strategies, yielding differing results. Higher-tier regional banks performed better in revenue diversification and cost management, while lower-tier regional banks are better able to maintain interest margins. Consolidation would create business synergy that could strengthen the revenue of the integrated banks.

Reinventing the business model may also help sustain earnings, especially when traditional banking is not as profitable as before. Sound regional banks usually expand into new opportunities that are needed by their communities, such as fintech and consulting services.

There is a silver lining to every crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic might force the Japanese regional banks to consolidate and shake up their business models to survive and thrive in the long run.