This piece is also published in Asia Times Financial on August 15, 2020.

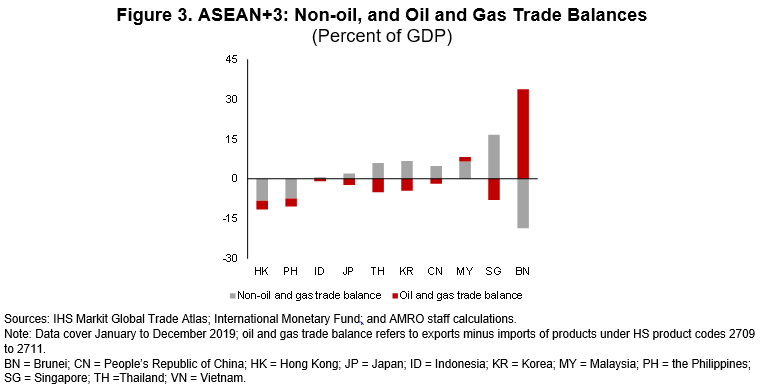

Oil prices have been hard hit by both weak demand and rising supply since the beginning of 2020. After reaching record low levels in April, the partial rebound in demand and reduction in supply led to some recovery (Figure 1). However, the rally may have run its course. A murky outlook for demand amid the COVID-19 pandemic, an increase in output, and record-high inventories are expected to drag oil prices down in the coming months.

A rollercoaster ride

The first seven months of 2020 saw oil prices move through three phases, driven mainly by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Phase One – the massive collapse. From January to April, the COVID-19 virus spread across the world, leading to lockdowns in many countries. The impact on oil demand was severe. The failure of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries and its oil-producing allies (known as the OPEC+) to agree on production cuts put oil prices on a slippery slope. Production volumes rose not only because existing cuts expired but also as a result of active increases to production by Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Russia. The excess supply subsequently used up storage capacity. These factors caused oil prices to fall—to their lowest levels in almost two decades for Brent and an unprecedented negative USD 38 per barrel for WTI.

Phase Two – the sharp rebound. In May and June, the OPEC+ implemented deep production cuts, of almost 10 percent of global pre-pandemic supply, which would gradually taper off through the second half of 2020 and into 2021. At the same time, economies around the world started to ease their containment measures, further boosting demand for oil. The sharp rebound saw Brent oil prices gain almost half of their earlier losses before stabilizing ahead of the OPEC+ meeting in early June, when further reductions in production was agreed upon by some of its members, such as Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. Non-compliant members consented to compensate by reducing production in the third quarter. Outside the OPEC+, the low oil prices made it difficult for the United States (more notably, the shale producers) and Canada to sustain existing levels of production, and oil rigs in these countries either shut down or curtailed production.

Phase Three – stagnation. Despite agreement on extending cuts, and voluntary and compensatory reductions in production, oil prices failed to achieve new highs immediately following the OPEC+ meeting. A pickup in COVID-19 infections, especially in the United States, cast a long shadow on demand recovery, while the deterioration in risk sentiment prevented any meaningful rally in oil prices. Although oil prices found support from US dollar weakness in late-July and were able to edge above their June peak, there is a clear lack of upward momentum.

A gloomy outlook

Looking forward, risks to oil prices are tilted on the downside.

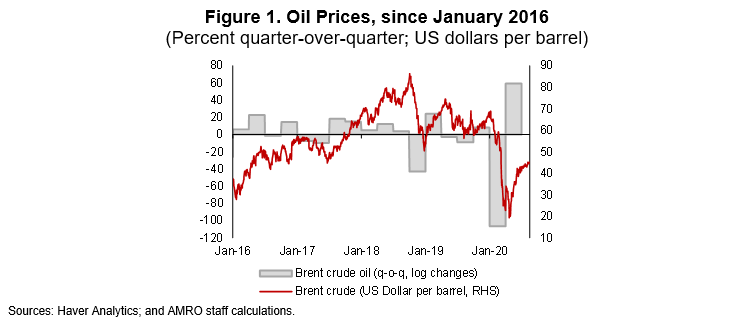

Demand for oil is expected to remain much lower than during pre-pandemic levels, and any sustained second wave of infections will likely reduce demand further. Supply is set to increase from the OPEC+, as well as from other producers that will resume production after the recent recovery in oil prices. Another significant drag on oil prices would be the sizeable build up in inventory in the first half of 2020, which is estimated to be sufficient for six quarters, based on the latest forecasts of quarterly supply and demand by U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) and OPEC (Figure 2).

Indeed, there could be upside risks to prices from an unexpected rise in demand or positive risk sentiment. Another potential risk is persistent US dollar weakness, which could result in oil prices (quoted in US dollars) rising from current levels.

But, given the uncertainty in the COVID-19 situation across the globe, we believe that a material and sustained move higher in oil prices may prove elusive in the coming months.

Impact on Asian economies

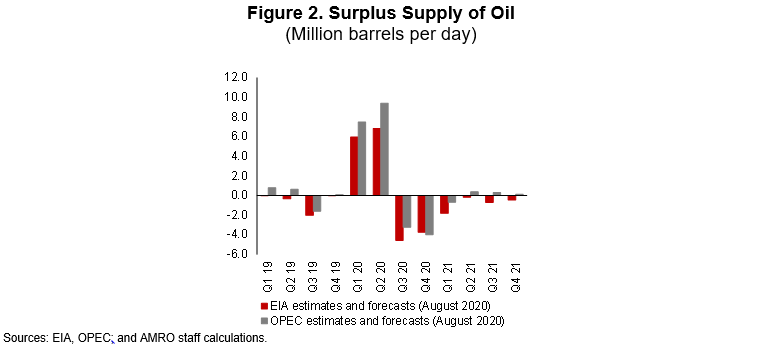

Lower oil prices has provided some relief to most Asian economies who are net oil importers, including China, Japan, Korea, and most ASEAN countries. The impact of lower oil prices can manifest through an improved balance of payments, lower inflation, and reduced fiscal burden of fuel subsidies (Figure 3).

The value of net oil imports shrank as a result of the sharp fall in oil prices earlier this year and the lower demand during lockdowns. However, the positive impact of reduced oil bills was eclipsed by the collapse in international trade, which has generally led to reduced trade deficits [surpluses] for trade deficit [surplus] countries. Lower oil prices may have contributed to disinflation, but the primary driver was likely the destruction in demand from the lockdowns. Similarly, any fiscal relief attributable to reduced oil subsidies was negligible compared to the fiscal support needed to facilitate economic recovery.

Nevertheless, lower oil prices have provided some relief to most countries in the region. In the unlikely event of a substantial and sustained rise in oil prices in the coming months, stagflation risks could come to the fore.