This is the first part of a three-part series of blogs describing ASEAN+3’s transition into the ‘new economy’. Read Part 2 and Part 3.

East Asia’s growth model is transforming, surely and rapidly.

Virtually all ASEAN+3 economies have pursued the conventional “manufacturing-for-exports” strategy with great success over the past few decades. All have achieved impressive growth catch-up at their respective stages of development.

And now, even as the catch-up effort continues, the region is transitioning to an even more broad-based development model in the “new economy”. China’s enterprises have become top regional and even global players in higher-end manufacturing, e-commerce, advanced logistics, professional services, and digital finance. The Philippines is transitioning from business process outsourcing to knowledge process outsourcing. Thailand’s highly competitive automobile industry and agro-food industry are adopting more technologically advanced production methods. Malaysia is redoubling its efforts to develop and apply modern Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) technologies in high-potential areas such as mechanical engineering, aerospace, and medical devices. Vietnam is stepping up efforts to move up the value chain by attracting more foreign direct investment (FDI) from Korea and other advanced economies, and developing digital standards, in order to take on more advanced manufacturing activities. All ten economies of ASEAN have joined the pilot smart cities initiative across the region.

What are the key drivers behind East Asia’s transition to the “new economy” going forward? There are several – some are global in nature, forcing change upon East Asia, and some are regional in nature, originating from national and regional efforts within ASEAN+3.

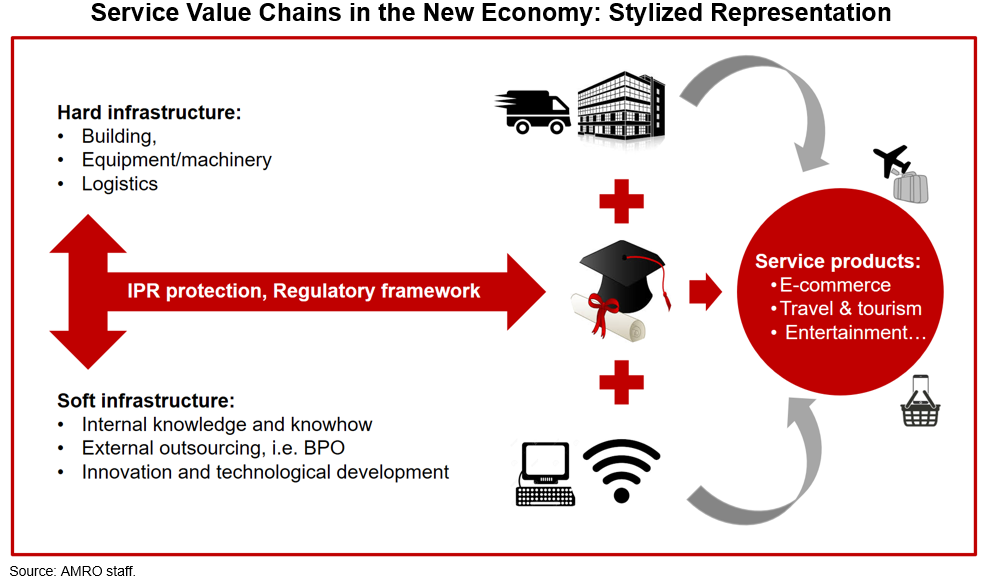

First, technological change is transforming the nature of the workplace and the way we consume goods and services. Many types of goods have become (embodied in) services over time. Where consumers used to buy tapes and discs to watch movies, they now stream digital files online, purchased using digital payments. And where families used to buy first sedans and then bulkier multipurpose vehicle (MPVs) as they expand, many are now opting to pay for daily transport as a service – with many customized options to pick from. On the production side, manufacturing of goods ranging from automobiles to clothing and footwear has become “machine lite, digital heavy”. Technological change occurring more gradually in the earlier phases has picked up pace in recent years and is forcing ASEAN+3 economies to upskill their workforces, upgrade their capital stock, and brace themselves for changes in the workplace and disruptions in the traditional business models. As a result, these economies are now positioning themselves to tackle the much more rapid pace of technological advancement sweeping across the global economy at this juncture.

Second, the rise of the middle class. While this is a global phenomenon, East Asia has accounted for the bulk of the increase in numbers and wealth of the global middle class over the past 15-20 years, and the trend is expected to continue for the next two decades at least. This affluent group, with increased spending power, and more demanding and varied tastes, will be a key driver of East Asia’s continued rebalancing from the old growth model where final consumption is driven by the western countries to one where domestic consumption and intra-regional demand play a much bigger role. Importantly, the final goods and services are also becoming more sophisticated: customized clothing, footwear, and accessories, experiential tourism, endless streams of online infotainment, ultra-fresh food delivered “just in time”, and charged to digital wallets.

Third, better connectivity. Years of underinvestment in infrastructure in several large ASEAN countries after the Asian financial crisis have led to poor infrastructure and connectivity that need to be improved if the region is to be able to take advantage of the technological revolution and rising middle class to move into the new economy. Improved transport and digital tracking systems are needed for all ASEAN+3 economies to shift quickly to smarter and more efficient public transport and food delivery. The more advanced ones have started developing “omni-channel” business models for retail business, integrating physical malls with virtual shopping platforms. Much better cross-border infrastructure, leveraging on regional initiatives such as the Master Plan for ASEAN Connectivity (MPAC), is needed to facilitate seamless trade in goods and services – with tourism, for instance, being one of the key beneficiaries. Professional services are being targeted as one of the most important growth opportunities in the years ahead, as more policymakers call for freer flow of higher-end human capital and services.

Fourth, commitment to globalization and multilateral engagement. Most ASEAN+3 economies do not have all the cutting-edge technologies across the various sub-sectors of advanced manufacturing and services, and so they have wisely continued to welcome FDI from advanced countries, even as they step up efforts to invest more in R&D activities and channel more of their own savings to intra-regional investments to benefit from the complementarities in the region. Going against the grain of the recent rise in protectionist tendencies in the US and Europe, ASEAN+3 as a bloc recognizes that it would be unwise and self-defeating to respond to trade and technology protectionism by enacting its own barriers to cross-border flows of economic and financial activity.

East Asian economies have been very successful in moving up the development ladder to middle- and high-income status based on the “manufacturing-for-exports” strategy and are now poised to move to an even more advanced “new economy”, based on the digital technology, rising middle class, and regional integration. But there are challenges that need to be overcome in this transformation process, which will be discussed in our next blog post.